- Folk Art Carved

- Features

- 3d Effect, Carvings (11)

- Antique (16)

- Antique, Solid Body (7)

- Carvings (544)

- Framed (10)

- Hand Carved (20)

- Hand Painted (47)

- Handmade (5)

- Limited Edition (4)

- Miniature (7)

- On Wheels (4)

- One Of A Kind (6)

- One Of A Kind (ooak) (215)

- Ornate (5)

- Personalized (5)

- Rare (4)

- Relief (5)

- Signed (155)

- Solid Body (14)

- Vintage (6)

- Other (2737)

- Format

- Bust (19)

- Cameo (2)

- Carved Wood (4)

- Carving (22)

- Diarama (2)

- Figurine (3)

- Full Body (3)

- Full Body Carving (5)

- Hand Carving (2)

- Light Sculpture (23)

- Mask (19)

- Mobile (3)

- Plaque (2)

- Sculpture (10)

- Shield (6)

- Statue (319)

- Wall Art (8)

- Wall Hanging (4)

- Wall Sculpture (8)

- Wood Sculpture (12)

- Other (3351)

- Material

- Acrylic, Metal, Wood (4)

- Bone (4)

- Brass, Wood (5)

- Burlwood, Wood (5)

- Carved Wood (4)

- Coconut (5)

- Driftwood (10)

- Driftwood, Wood (3)

- Glass, Wood (3)

- Mahogany (3)

- Metal (7)

- Metal, Wood (3)

- Pine (5)

- Resin (9)

- Solid Wood (6)

- Stone (12)

- Wood (2259)

- Wood / Woodenware (5)

- Wood, Glass (4)

- Wood, Metal (6)

- Other (1465)

- Style

- 1970s (10)

- 3d, Cartoon (11)

- American (42)

- Americana (165)

- Americana, Folk Art (11)

- Antique (15)

- Asian (11)

- Black Folk Art (33)

- Black Forest (25)

- Cane (24)

- Country (28)

- Folk Art (984)

- Naive, Primitive (96)

- Primitive (14)

- Rustic (11)

- Rustic / Primitive (26)

- Tramp (17)

- Tramp Art (22)

- Vintage (22)

- Walking Stick (45)

- Other (2215)

- Subject

- Type

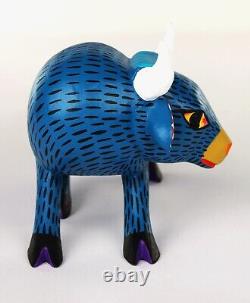

Oaxacan Wood Carving Armando Jimenez Bull Toro Oaxaca Mexican Folk Art Alebrije

COOL BLUE LONGHORN BULL TORO BISON BUFFALO OAXACA WOOD CARVING BY THE WORLD-FAMOUS OAXACAN WOODCARVING ARTIST ARMANDO JIMENEZ. WHIMSY AND A SENSE OF MOTION!!

This fantastic bull toro wood carving has all of the whimsy and charm that we love in Mexican Folk Art! Armando Jimenez is the grandson of the master carver Manuel Jimenez, who is credited with creating the whole movement of the Oaxacan wood carvings, also sometimes referred to as alebrijes (although the term alebrije is more appropriately attributed to the paper mache figures from the Linares Family of Mexico City). Armando has traditionally worked next door to his brother Moises, and the carvings of both of these very talented men are in high demand. What a great way to support a living legacy, and an art form that has been passed down within the family.Armando and Moises pieces, while adhering to the traditional painting style of their family, shows incredible range of creativity in the whimsical animals depicted... Animals often not native to Oaxaca. I have always loved these toro wood carvings from Armando Jimenez, and this one has extra charm and appeal.

Full of shear fun and beauty. From the carved details of the curved upwards horns to the polka dot detail on the top of the head in between the horns, the bashful face, the droopy ears and the carved in eyes and hooves and the tail that was carved as part of the wood that became the hind leg...

This gorgeous piece is just full of joy! The carving itself is full of a difficult to achieve sense of movement in the positioning of the legs, the forward-facing head, intense deep-set eyes and the swiping downward tail.

There are no removable parts. This toro will make the perfect addition to your collection. It is signed by Armando Jimenez and his wife Antonia, as well as their son Alejandro. This carving is even better in person. With the white background, the cool detail of the horns fades into the background in the pictures.

Approximate Measurements: 5 5/8" high x 8 3/4" long x 5 deep. Oaxacan wood carvings start out traditionally with a piece of Copal wood, either a piece of the trunk, or one of the magnificent branches of the tree.

The Copal wood is a soft wood that is similar to a balsa wood, but the Copal is indigenous to Southern Mexico. After the animal wood carvings from Oaxaca became extremely popular, the Mexican government stepped in to control the supply of the wood and even created a biosphere to preserve the species.

Artists are no longer able to cut trees down though and must pay increasingly higher prices to obtain a supply of this wood from authorized dealers who maintain a cap on the supply. Currently many artists recognize the importance of preserving these trees and have communal programs in the villages to replant the Copal, since the tree actually takes about 25 years to mature. The Copal tree takes on a cultural and religious significance in the community as well, since the sap of the tree is used for making incense that is often valued for its ceremonial usage. The figures are first carved while the wood is green, and the artist is able to carve out fantastic details since the wood is so soft. Other wood can be used, so at times you will find cedar or pine, but Copal is the most commonly used wood.

The rough outline is done with a large machete, and the positioning of the figure is often determined by the shape of the piece of wood that is sourced. A carver can take a look at the piece of wood and envision just what kind of animal they will be able to carve, and how to position it. Further refinements to the carving are done using gradually smaller rustic knives, usually fashioned locally from whatever is available.After the figure is carved, it is sanded smooth and left to dry. The drying process can take several months if it is a large piece. While it is drying, the wood will often crack, and then the artist will fill these cracks using wood chips and filler, before again having to sand the figure down. The most valuable carvings are often one-piece carvings, carved out of a single piece of wood, but you will often find removable parts like tails and ears, that make transporting these a little easier.

A sense of motion in the piece is another sign of quality, as it is also a measure of the degree in difficulty achieved in the particular piece. Twisted bodies, turned heads, raised legs, curved bodies and tails are all indications that an extra amount of work went into the piece of art. Many of the older pieces were painted with natural analine or coal-based dyes, but these often faded over time, so most artists switched many years ago to acrylic paint.

With the acrylics, more cheerful colors can be achieved, and the paint is more long lasting. We love the sense of color in these cheerful carvings!Oaxacan wood carvings became commonly referred to as Alebrijes, especially after the movie Coco came out, but the term alebrije actually is attributed to the Linares Family who create fantastical paper maiche figures in Mexico City. The term was widely used in Oaxaca after a joint exhibition that was done where both Pedro Linares of Mexico City and Manuel Jimenez of Oaxaca were present.

Manuel Jimenez became the driving force behind Oaxacan wood carvings and is said to have been influenced by the colors that he saw in the work of Pedro Linares. But the actual term "Alebrije" is actually said to have come to Pedro Linares in a dream about fantasy creatures. There is much debate currently in Mexico about the use of this terminology, and who should have the right to use it.

As a result, in Oaxaca, you will also see the terms Tonas and Nahuales, which refer to spirit animals and mystical creatures that take on both human and animal forms. Another term used is Tallas de Madera, or simply wood carvings from Oaxaca. Popular culture, however, has made it more difficult for the artists not to use the term Alebrije when referring to their carved figures, since more and more people have become accustomed to the terminology. It will be quite interesting to see how this plays out in the future.